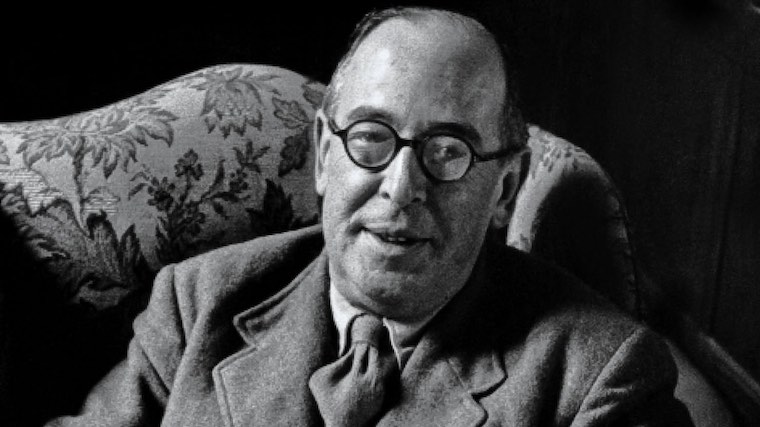

It’s always a joy to read biographies. Its an even bigger joy to read autobiographies where the author explains their conversion to Christ. Last week I read “Surprised by Joy” by C. S. Lewis. Last Monday I posted a synopsis of his conversion from atheism to Christianity, but I also wanted to follow this up with some of my favorite quotes from the book which are relative to his conversion, and some of which are philosophically interesting.

The truth has a way of breaking through. Lewis expressed this beautifully in one of my favorite quotes, which is well known:

A young man who wishes to remain a sound atheist cannot be too careful of his reading. There are traps everywhere, “Bibles laid open, millions of surprises,” as Herbert says, “fine nets and stratagems.” God is, if I may say it, very unscrupulous. (p191)

A young man who wishes to remain a sound atheist cannot be too careful of his reading. - C. S. Lewis Click To Tweet

Clearly God uses a variety of means to draw people to Himself. For Lewis, Christians seemed to surround him as if they were conspiring against his atheism, and they seemed to have cornered the market on good writing. Here is another from a bit later on:

All the books were beginning to turn against me. Indeed, I must have been as blind as a bat not to have seen, long before the ludicrous contradiction between my theory of life an my actual experiences as a reader. George MacDonald had done more to me than any other writer; of course it was a pity he had that bee in his bonnet about Christianity. He was good in spite of it. Chesterton had more sense than all the other moderns put together; bating of course, his Christianity. Johnson was one of the few authors whom I felt I could trust utterly; curiously enough, he had the same kink. Spenser and Milton by a strange coincidence had it too. Even among the ancient authors the same paradox was to be found. The most religious (Plato, Aeschylus, Virgil) were clearly those on whom I could really feed. On the other hand, those writers who did not suffer from religion and with whom in theory my sympathy ought to have been complete – Shaw and Wells and Mill and Gibbon and Voltaire – all seemed a little thin; what as we boys called “tinny” It wasn’t that I didn’t like them. They were all (especially Gibbon) entertaining; but hardly more. There seemed to be no depth in them. They were too simple. The roughness and density of life did not appear in their books. (p213-214

In the next paragraph he summarizes this in his own words by saying:

The only non-Christians who seemed to me really to know anything were the Romantics; and a good many of them were dangerously tinged with something like religion, even at times with Christianity. The upshot of it all could nearly be expressed in a perversion of Roland’s great line in the Chanson – “Christians are all wrong, but the rest are bores” (p214)

Lewis was also insightful when it came to analyzing his experiences. On aesthetic experiences he wrote:

The surest way of spoiling a pleasure was to start examining your satisfaction. But if so, it followed that all introspection is in one respect misleading. In introspection we try to look “inside ourselves” and see what is going on. But nearly everything that was going on a moment before is stopped by the very act of our turning to look at it. Unfortunately this does not mean that introspection finds nothing. On the contrary, it finds precisely what is left behind by the suspension of all our normal activities; and what is left behind is mainly mental images and physical sensations. The great error is to mistake this mere sediment or track or byproduct for the activities themselves. (p218-219)

This new dovetailing of my desire-life with my philosophy foreshadowed the day, now fast approaching, when I should be forced to take my “philosophy” more seriously than I ever intended. I did not foresee this. I was like a man who has lost “merely a pawn” and never dreams that this (in that state of the game) means mate in a few moves.(p222)

Of course, this melding led Lewis to eventually believe that there is a God.

The real terror was that if you seriously believed in even such a “God” or “Spirit” as I admitted, a wholly new situation developed. As the dry bones shook and came together in that dreadful valley of Ezekiel’s, so now a philosophical theorem, cerebrally entertained, began to stir and heave and throw off its gravecloths, and stood upright and became a living presence. I was to be allowed to play at philosophy no longer. It might, as I say , still be true that my “spirit” differed in some way from “the God of popular religion.” My Adversary waived the point. it sank into utter unimportance. He would not argue about it. He only said, “I am the Lord”; “I am that I am”; “I am.”(p227)

The first part of his conversion is recounted as:

In the Trinity Term of 1929 I gave in, and admitted that God was God, knelt and prayed: perhaps, that night , the most dejected and reluctant convert in all England (p228-229)

In the Trinity Term of 1929 I gave in, and admitted that God was God, knelt and prayed - C. S. Lewis Click To Tweet

But, by Lewis’ own admission this was merely a conversion to theism. His conversion to Christ followed later and is recorded simply:

I know very well when, but hardly how, the final step was taken. I was driven to Whipsnade one sunny morning. When we set out I did not believe that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, and when we reached the zoo I did. (p237)

For Lewis, joy, that fleeting aesthetic experience, turned out to be,

valuable only as a pointer to something other and outer. While that other was in doubt, the pointer naturally loomed large in my thoughts. When we are lost in the woods the sight of a signpost is a great matter. (p238)

What ultimately derailed Lewis’ atheist train was that he recognized that his philosophy was reductionistic, unable to adequately explain his everyday experiences. What did he do? Having recognized he was suppressing the truth, he repented and agreed with what God about himself and about God.